It isn’t every day that one receives the oportunity to share something that means so much. Telling the story of a recently passed loved one could be a difficult task. But as I consider the life and experiences of my late grandfather I am sruck by one realization; my grandfather was a man who lived profoundly well.

He was a man who experienced the gamut of life from wealth to extreme poverty. He started with nothing and eventually left behind a legacy that could be described as enviable. Enviable not because of his amassed wealth or vast influence. Enviable because at the very end of his life he was simply content.

As such this difficult task of telling my grandfather’s story is also an important one. Because what could be more important than sharing the values and priorities that allowed a man to die well? There isn’t anything more that any of us could ask for than contentment and peace at the end of our life.

So here is the story of a my grandfather. A man who knew how to live.

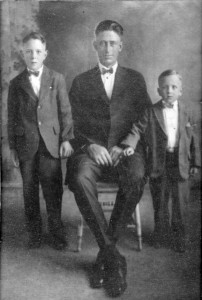

Lloyd Gerald Lockhart was born into a situation that was fairly typical for a child of the era. He came into the world on a mid-August day in 1921, in a tiny house along the Elk River. Before he was two years old his father, James Lockhart, uprooted the family from the Yampa Valley and moved to Casper, Wyoming, in hopes of finding work related to the oil boom. Here the family lived in a small house alongside the railroad.

While growing up, Lloyd and his brothers – Clyde and Jack – possessed an amount of liberty that might be considered neglectful in our time. Standards were different, however, and families did what they could to make ends meet. For instance, in their spare time Lloyd and his brothers would scour the rail yard that made up their neighborhood for empty whisky bottles. Then they would sell the bottles to bootleggers in order to augment the family income, often spending a little of the money by going to the movies before heading home. At one point Lloyd and Jack were put into the care of a program with the purpose of helping feed and care for underprivileged children. The nutritious food and warm accommodations came at price, however: Having a dutiful adult nearby to keep an eye on mischievous children wasn’t a situation that appealed the Lloyd’s independent spirit. It didn’t take long, therefore, for Lloyd to decide that it was time for him and Jack to move on. They didn’t tell anyone about their departure – after all it was more like an escape – and eventually even the sheriff became involved in the search. The boys had gone swimming, it turns out. Now days the thought of a 1st Grader and his brothers selling scrap to illicit substance manufacturers seems highly inappropriate. The situation was no doubt far from ideal, but at the very least Lloyd learned some skills that he would put to good use for the next 75 years.

This life of independence wasn’t completely one of going to movies and having Huckleberry Finn-style adventures with his brothers. When Lloyd was 7 years old his father died after spending six months ailing in the hospital. Lloyd’s mother, Ruth, remarried but this new situation was anything but conducive to a happy childhood. To make matters worse, Ruth passed away within three years of James’s death. At just 10 years of age and an orphan, Lloyd was sent back to the Yampa Valley with his brothers to live with their uncle. Here he was put to work in the hay fields, working ten hour shifts driving teams of horses and operating the stacker. These conditions didn’t last, as it didn’t take long for Lloyd to decide that if he was going to be working hard he might as well be working hard for himself. Consequently, by the time he was in high school he had moved into town and was supporting himself with a job at Irene’s Café.

Some might have considered such circumstances unfortunate, but if anything Lloyd knew how to make the most of whatever situation in which he found himself. Consequently, his high school schedule wasn’t that of a typical teenager. His day began at 5 a.m. when he got up to start the kitchen fire and wake the wait staff. When necessary he would even start cooking meals before heading off to school. By the time school was out he had to hurry back to the café in order to catch up washing the dishes. He would work the night shift so late into the night on Friday nights that he would go straight from doing Friday’s dishes to making Saturday’s breakfast. During this time his grades suffered, yet it is doubtful that Lloyd would have placed the blame on his circumstances. Of his childhood Lloyd once said,

After all, despite the added stress of supporting himself Lloyd managed to participate in the school activities that were important to him. He was often voted class president and student body president, and was also captain of the basketball team. In fact, once when he was put on academic probation because of poor grades the rest of the basketball team went on strike until he was allowed back.

It wasn’t just being the right hand man at Irene’s and high school sports that kept Lloyd busy. He also scraped together a means by digging up gardens in the summer, shoveling snow in the winter, and by doing janitorial work whenever he could. Working hard with relentless hours wasn’t so bad, so long as he was making progress. One season he was renting a “room” on someone’s back porch and basically slept outside all winter. By the end of high school, however, he was able to rent a room with his brother for $20.00 a month. Not only that, when he graduated high school in 1939 he had saved up enough money to “retire” for the first time, with a whole $90.00 in the bank. It was during this time as well that he became the first person in Steamboat to own a Harley Davidson motorcycle. He was also the second person in Steamboat to own a Harley Davidson, but that is a different part of the story.

Lloyd’s hard work and determination wasn’t just for the money, however. A man has to have food and a place to sleep, and Lloyd worked six days a week for that. But once again Lloyd’s ambitions were focused by priorities. As such, this tiring schedule was not enough to send him sleeping in on a Saturday morning. This practically constant work was so that he could take all day off on Saturday and therefore have time for what was truly important to him, and nothing could skeep him from spending all day on Saturday’s with his first and only love, his high school sweetheart – Annabeth.

After graduating high school Lloyd began work at a creamery on Emerald Mountain, which once again began at five in the morning and kept him busy for about half his time. The other half of the time he spent working for his brother, Clyde, who had opened a restaurant of his own. It was here that Lloyd earned a reputation for being a great cook, a reputation he maintained for the rest of his life.

Within two years Lloyd had saved up enough money to marry Annabeth and put a $300 down payment on a house. This 20-year old orphan who had started out collecting bottles had done quite well for himself. Lloyd had never been one to compare himself with others and he had certainly never been one to complain, but for those of us looking at his life from the outside, his circumstances were finally looking up.

Lloyd and Annabeth were married in November of 1941. Two weeks later they heard the news that Pearl Harbor had been attacked and the nation was going to war.

Consequently, within the first few months of their marraige, Lloyd had been drafted and was sent off to boot camp. Annabeth moved all over the country and found work where she could in order to be near him while he was training. Then with his training complete, in 1944 Lloyd was shipped to Europe. He and Annabeth wouldn’t see each other again until 1946.

During the war and the occupation Lloyd still managed to do that extra little bit to make the most out of what many would have considered to be an unfavorable situation. American soldiers were issued cigarettes and chocolate in their rations. During the post-war occupation, when American and Russian soldiers operated in close proximity, there arose a very high demand for American-made cigarettes and chocolate which were considered to be of superior quality than those possessed by the Russians. Consequently, rather than consume these commodities as he rightly deserved, Lloyd sold them whenever he could to his Russian counterparts. After a year of occupation duties he had sent home enough cash for he and Annabeth to buy their first car. Apparently it didn’t turn out to be a very good car, “the clutch was always going out”, he explained, but a bad car sure was a better alternative to developing a smoking habit.

Upon his return from Europe, Lloyd and Annabeth lived in Denver. Here Lloyd attended night school for electrical engineering and worked full time for Monarch Airlines, which eventually became Frontier Airlines. Despite achieving consistently good grades during his time in college, Lloyd once again decided that academia didn’t warrant a high level of priority in his life goals. So without a diploma the family returned to Steamboat in 1953, this time with their two children, Tyrone and Delano. For about ten years Lloyd worked various jobs in the Yampa Valley, including working at F.M. Light & Sons, test driving cars in winter conditions on Rabbit Ears Pass, and running a Texaco bulk station. In 1964 he had the opportunity to buy F.M. Light & Sons from his father-in-law, and his lifelong practice of hard work and faithfulness ensured that this venture was a continued success.

After running and managing the store for some time Lloyd continued the tradition and sold F.M. Light & Sons to his sons, Tyrone and Delano. This hardly spelled retirement, however, as it was in Lloyd’s nature to always have something going on. What it did do was give him and Annabeth the opportunity to begin traveling. And like his life thus far, these travels took on a nature that was anything but akin to vacation. Lloyd and Annabeth traveled to exotic locations, like the Andes, India, and the Middle East. They also traveled to locations which, under the global political conditions of the Cold War, made travel quite difficult. But this is Lloyd, you understand, and no Iron Curtain was going to keep this cowboy out of Red Square. He and his cowboy hat also became quite a big hit in China.

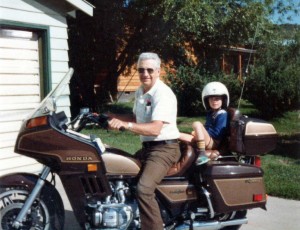

It wasn’t until he was in his sixties that Lloyd’s life finally began to take on a pace that would be considered more ordinary. Becoming a grandparent has a way of doing that to a person. Even so, he and Annabeth would oftentimes be found roaring around the countryside on their motorcycle. Annabeth would wear a helmat. Lloyd, of course, road with a cowboy hat.

This was the era of his life in which I grew to know Lloyd. Back then I didn’t know all of these particulars of his life. To me he was just Pop, a guy about the same build as a man called John Wayne who I had seen in some movies, and who wore the same cowboy hat as well. I would playfully poke him in the stomach and call him fat, and he would act all offended, call me a skallywag, and then chase me around the room with the supposed intention of tickling me. He usually ended up on the floor pretending to be tickled by me.

To a five year old kid playing with his grandpa, none of these stories of his life would have mattered to me even if I had known them. What mattered was the time he spent with me. And one of the most remarkable features of his life is that Lloyd realized this; that relationships are what matter.

One of the ways in which Lloyd and Annabeth cultivated relationships was by feeding people. In fact, some of the most prevelant memories of my childhood are mealtime with my grandparents. Pop was a tireless and masterful host. I cannont count how many times I finished three pieces of french toast and had barely swallowed some orange juice when another piece landed on my plate; “here you go, cowboy. Looks like you need some more scrambled eggs too.” And I won’t even go in to how great his grilled cheeese sandwhiches were.

While Pop loved to give, the primary way in which he poured value into relationships was by being present. No matter what the situation or the event, he was always there. He always made the effort and went the extra mile.

Even as his health deteriorated and his strength dwindled to almost nothing, it was apparent that he cared. As he was dying he continued to cary out his actions of selflessness and love as he always had. It was profoundly telling of his nature, while he was in chronic pain and acutely weak, when we put him in bed and he would muster the strength to grip the hand of whoever had helped him there, and he would always ask “How are you doing? “How is your family?” Because that’s what Lloyd was about. He cared about and was interested in you.

That’s the story of an orphan who became a great grandfather, a man who started with nothing and eventually became our Pop. And if there ever was a measure of a man’s success, it would be to become a Pop just like our Pop was.